Sub species.

European Dark bee Apis mellifera mellifera L'abeille européenne or Abeille noire.

Italian honey bee Apis mellifera ligustica Abeille italienne.

Carniolan honey bee Apis mellifera carnica Abeille carniolienne.

Spanish honey bee Apis mellifera iberiensis Abeille ibérique

Hybrid, Buckfast honey bee – Apis hybrid

It’s doubtful that there are many pure colonies of Apis mellifera mellifera in France although on L'Ile de Ouessant, Brittany there is the Association pour la Conservation, la sélection et le développement de l'Abeille Noire (écotype breton). Abeille noire Breton which is far enough from the mainland to maintain genetic purity.

The other sub species, Italian, Carniolan and Buckfast are not originally native and are selectively bred for Bee keeping purposes in France. Although some pure first generations may be found "unmanaged" most feral honey bees are hybrids of varying genetic makeup. The Spanish honey bee is probably absent.

Honey bees are “social bees” which is to say they live as a colony containing a Queen, workers, (sterile females), and for part of the year drones, (males). They are the only bees in Europe to maintain a continuous colony that survives from one year to the next and requires a complex biology as the colony population requirements must be regulated throughout the year according to seasonal and other needs. They require an enclosed space in which to construct their wax combs which are used for storing honey, pollen and raising new brood.

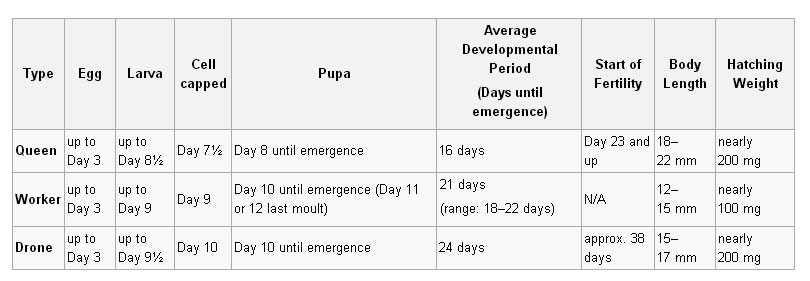

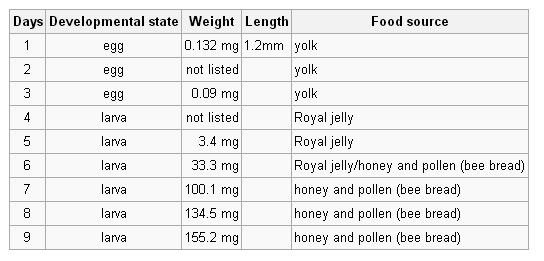

They have a complete metamorphosis with four life stages.

They start as eggs, which are very small.

The egg hatches into a larva which is like a maggot and grows rapidly.

When the larva has grown it changes into a pupa which cannot move or eat.

The pupa changes into an adult bee.

A fertile queen is able to lay fertilised or unfertilized eggs.

An unfertilised egg contains a unique combination of 50% of the queen's genes and develops into a haploid drone, (male).

A fertilized egg can develop into either a worker, (sterile female), or a virgin queen depending on how the larva is fed.

For the first two days, all larvae are fed a diet of royal jelly. Beginning the third day, worker larvae are fed honey, pollen and water, while the larvae destined to become queens continue to receive royal jelly throughout their larval lives.

Workers have various duties depending on age and time of year but broadly basic work is divided into foraging, housework, nursery work and guarding.

Drones only function is to try and mate with Virgin Queens, otherwise they are freeloaders simply moving from colony to colony taking their free food.

A new Queen will be required either to replace an old or unsatisfactory Queen, a Queen that has been killed or when the colony is preparing to swarm.

The typical Queen cell is specially constructed to be much larger, and has a vertical orientation and will usually be hung at or near the base of a comb when for swarm preparation, however when a new Queen is urgently required they will produce emergency cells. These cells are made from a cell with an egg or very young larva and are usually near the middle of a comb having to protrude from the comb before bending towards the vertical. In all cases several Queen cells will be created, perhaps as many as 15 or more when swarming is about to take place.

A year in the life of a Bee colony.

Much depends on where in France the colony is and what the weather conditions are but generally as winter starts to end the Queen will start to increase egg/brood production. She will have stopped completely during very cold periods when the colony will have clustered together. Brood production will increase rapidly as spring arrives with warmer days and the first flowering plants and trees. Generally sometime around the middle of April – end of May the colony population should be at full strength – what this is in numbers will depend on the specific genetics of the colony and how much space they have but could be 70,000 bees or even more.

At this point it is likely that the colony will prepare for swarming and then usually on a warm day, often between 11am and 3pm, the existing Queen will leave the colony with about 50% of the colony, fly a short distance and form a cluster hanging on just about anything, a bush, a branch, a fence etc. Mostly this will be comprised of young bees that have filled up with enough honey to meet the needs of the coming 10 to 14 days while they find and start to construct a suitable “new home”.

In the original colony a new Virgin Queen will soon hatch and after a few days she will be ready to make her mating flights, usually two or three on different warm afternoons when she will quickly orientate the location of the colony, then fly high to where the Drones will be congregating waiting to mate. She can mate with as many as 25 Drones during those few flights storing their sperm and each of the Drones will die in the act as the process of insemination requires a lethally convulsive effort.

If she is successful she will have enough sperm to last 3, 4 or more years producing up to 6 million workers.

The new and old colonies will build back their numbers; both will have had a break in their brood cycle for a period of time with a corresponding reduction in population numbers. Once population numbers are sufficient they will be maintaining them whilst storing any honey that is excess to daily requirements to take them through the winter. As the end of summer arrives and autumn approaches the Queen will reduce the number of eggs produced and the colony numbers will reduce for winter, Drones will no longer be produced, existing Drones may be denied access to colonies and die. By the end of October there will be little, if any, forage available and the colony will become increasingly inactive as winter arrives.

Threats.

There are a number of natural hazards that can be identified which could result in colony failure and theoretically these would result in a stable number of colonies over time in an unmanaged or feral situation.

This is not the same when bees are kept in a highly manipulated and managed manner as is often the case with much bee-keeping, (hobby or commercial), where the natural life of the colony is overridden and interfered with.

Principle natural causes for colony failure.

1. There is about a 10 to 15% chance that a Virgin Queen will fail to mate successfully usually as a result of failing to find her way back to the colony when on mating flights or, although less likely, by being killed or eaten at this time.

2. The Queen finally exhausts her supply of sperm without having been replaced and starts to lay only infertile eggs becoming a “Drone layer” with no more new workers.

3. The Queen dies or fails during the winter period when there is no chance of raising or mating a new Queen. This is most likely to occur with Queens that are in their third year that tends towards 1 in every 3 or 4 swarms failing in their first winter.

4. A swarm fails to find a suitable cavity to house itself and either chooses an unviable location, (too hot, too small etc.), or makes comb in the open suspended from a branch or such like where it is doomed to fail exposed to the elements in winter - photo below

5. Starvation in winter / early spring due to insufficient honey stores. This is rare in natural colonies except following exceptionally bad weather the preceding summer.

On average an unmanaged or feral colony will last between 6 and 7 years BUT due to the scent of the residual pheromones, wax and propolis it will likely attract another swarm in the future.

Pests, parasites and diseases can play a role in the life of a colony although only a few are significant or likely to be terminal.

Nosema apis is a unicellular parasite of the class Microsporidia, which are now classified as fungi or fungi-related. It has a resistant spore that withstands temperature extremes and dehydration and can cause winter colony failure. It is usually associated with long, cold wet periods in the flying seasons or very damp conditions inside the colony during winter. Nosema can cause queen supersedure, winter colony loss or weak, dwindling populations that struggle to grow numerically.

Dysentery is a condition resulting from a combination of long periods of inability to make cleansing flights (generally due to cold wet weather) and food stores which contain a high proportion of indigestible matter. Once faecal matter starts to be spread inside the colony it can rapidly bring about the end of the colony.

American foulbrood is caused by the spore- forming Paenibacillus larvae ssp. larvae (formerly classified as Bacillus larvae), is the most widespread and destructive of the bee brood diseases. This disease only affects the bee larvae but is highly infectious and deadly to bee brood. Infected larvae darken and die and the spores become spread throughout the colony. When the colony becomes weakened from the infection, robber bees may enter and take contaminated honey back to their hives thereby spreading the disease, although it is mainly a disease that presents in managed colonies where it is spread from hive to hive by bee keepers using contaminated hive parts or hive tools.

The Asian Hornet still has the jury out on whether it is a major threat and there is currently a lack of reliable data. Asian Hornet in France

Other fairly common or very common issues are Acarine (Tracheal) mites, Wax moths, European foulbrood, Chalkbrood, Stonebrood, Deformed Wing Virus and Varroa mites, with Varroa mites now endemic in France since their presence in the country was first observed in 1982. None of these present a serious threat to Honey bees in France.

Pesticides may be a local issue but they don’t currently appear to be having an effect overall on the unmanaged colonies.

The natural place for a honey bee colony is in a cavity in an old tree, rock face and for the last 1000 years or so in France cavities in the walls of stone buildings. Initially those would have been churches, castles and other fortified structures and although colonies are still found in these places they are increasingly to be found in house walls, chimneys and roofs, especially old stone houses that have had the grenier, (loft), converted to living space creating restricted spaces between roof and ceiling. People are often alarmed to find a bee colony in their roof but providing the entrance to the colony is somewhat above head height it shouldn’t present any problems and won’t harm the structure of the building.

Honey bee colony constructed between shutters and window in France. These can be removed but the level of difficulty will depend on how long it has been there

Removing Honey bee colonies from buildings, walls or trees can only be achieved with full access to the entire comb structure.

There is no level of protection for Honey Bees in France apart from this law passed in 1942.

Loi n° 993, du 9 novembre 1942, relative à l'interdiction de la destruction des colonies d'abeilles par étouffage.

Nous, Maréchal de France, chef de l'état français, le Conseil des ministres entendu, décrétons:

Article premier.

La destruction des colonies d'abeilles par étouffage, en vue de la récupération du miel ou de la cire, est interdite.

Seule est autorisée la destruction des colonies fondées par des essaims volages qui constitueraient une gêne pour l'homme ou les animaux domestiques.

Overall the situation for honey bees in France would appear to be stable in the regions where they would normally live without human intervention and it is likely that the feral colonies will continue to be augmented by swarms from apiaries.