European Mink

Mustela lutreola

Vison d’Europe

The European Mink in France

is one of Europe’s most endangered mammals and is also extremely easy to confuse with the American mink, Mustela vison, (Vison d’Amérique in French). The fur is normally a very dark brown with a small band of white around the mouth and sometimes on the throat; this marking can assist in identification but it is by no means certain. Although the smaller size of the European mink may also help to distinguish it from the American mink, often the only reliable method is by skull and/or bone measurements or genetic analysis. It is also possible to confuse the European mink with the Polecat, Mustela putorius (Putois in French) in some of its forms.

Males and females of the European mink look very similar, the males are however up to 75 or 80% larger probably to enable them to compete for females and territory; the females only need to protect and feed their young. Males weigh from 600g to 1kg, females 400g to 800g.

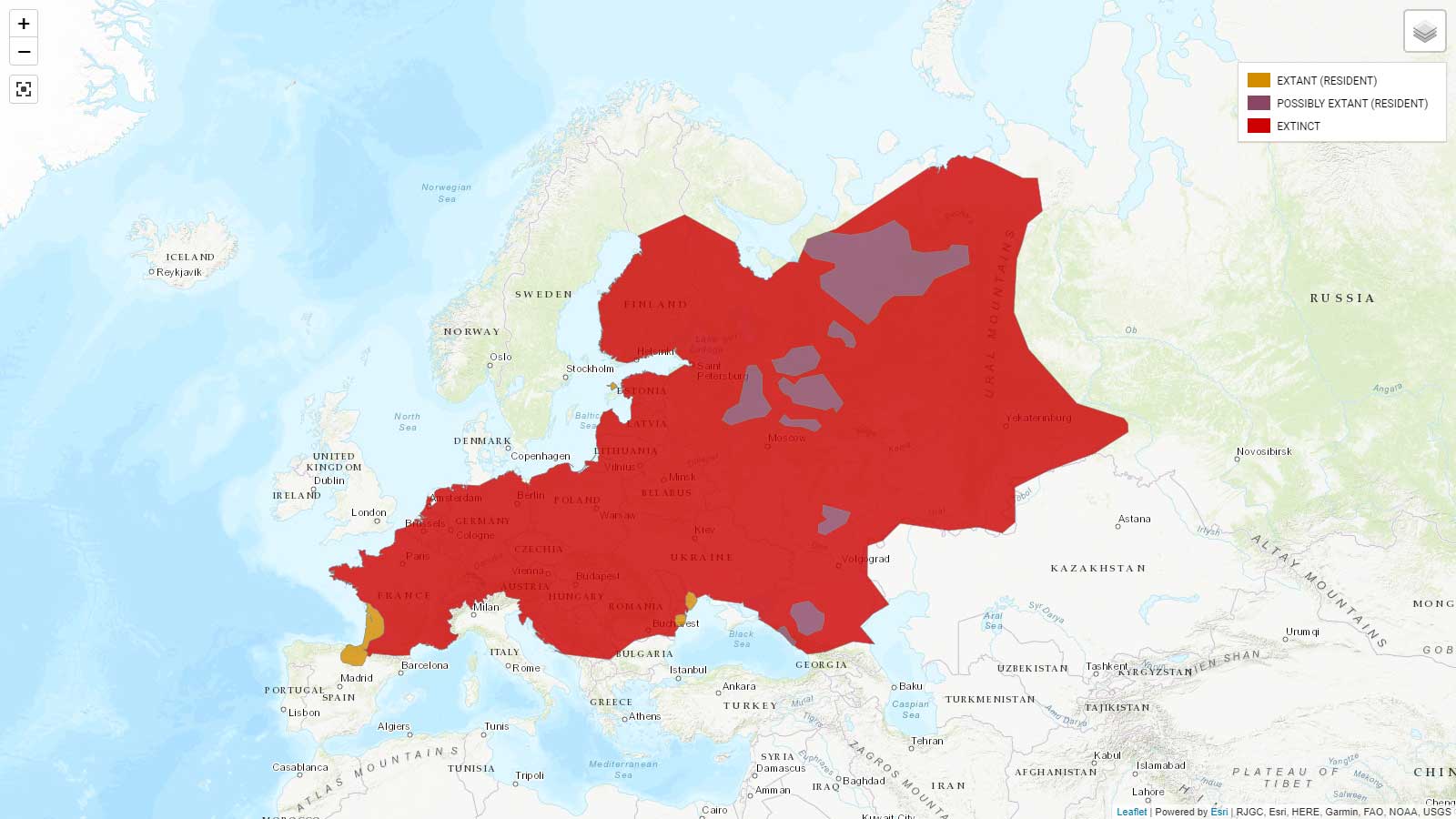

History. At the beginning of the 20th century before its present decline the European mink occurred in non-Mediterranean France and in adjacent provinces of north western Spain, in northern and eastern Germany, Poland, eastern Austria, Czechoslovakia, eastern Yugoslavia, Hungary, Bulgaria, northern Romania, central and southern Finland and the western parts of what was the USSR reaching as far as the Urals and the Black Sea. The decline was already evident by the 1950’s and between then and 1990 the decline was very rapid leaving only small numbers in parts of Eastern Europe, North West Spain, South-Western France and possibly Greece.

The reasons for its rapid decline are still not fully understood it would seem, although there is an obvious connection with the introduction of the American mink in the 1920’s, other hypotheses include hunting, urbanisation, water pollution, general loss of habitat, poisoning and trapping meant for other species (coypu for example) and also the possibility of a new or introduced disease.

A National action plan for the European mink in France was introduced in 1998 and is coordinated by SFEPM. (Société Française pour l'Etude et la Protection des Mammifères). In Oct 2004 as a result of their research they denounced the use of chemical poisoning having found that 10% of Otters and European mink found dead in Aquitaine were poisoned by bromadiolone or chlorophacinone two (1) anticoagulants used regularly to poison coypu and muskrats, as well as other rodents.

Behaviour. Mink are mainly nocturnal, tending, but not always, to spend the day in their dens, coming out at night to prey on small mammals, birds, insects, fish, and frogs, in fact almost anything it can overpower and eat. Unlike the otter it is a poor diver and can not hold its breathe for as long, making it harder to catch fast fish.There is no social structure, males and females only coming together at the time of rut, which can be aggressive between the sexes, after coupling the females remain alone to bring up the young following an uncertain gestation period thought to be between 35 & 42 days (Novikov) or between 43 & 70 days (Stroganov). The female gives birth to 2 – 7 young, born blind, in April - June and raises them in a den, milk feeding for about 5 or 6 weeks. The young leave the den after 12 – 18 weeks and reach maturity at about 1 year. Life span in the wild is about 6 years and up to 12 years in captivity

The mink uses a territory of up to 15 kilometres or more of river using many different dens which are in cavities in the ground, in tree roots, hollows in trees and old tunnels that have been vacated by other mammals, sometimes forcibly. The mink is not a great land traveller and the dens are rarely more than 5 meters from the water – the maximum distance a mink will normally range from water being about 100 meters. They remain active throughout the year with no period of hibernation..

Status: Currently found only in the 5 departments of Aquitaine (Dordogne, Gironde, Lot et Garonne, Landes et Pyrénées-Atlantiques) and in the south of Poitou-Charentes (Charente et Charente-Maritime).

Listed as Critically endangered by the IUCN

(1) These anticoagulant rodenticides are highly toxic to many species and, for example, when consumed in sub lethal quantities they build up in the livers of Barn Owls and widely accepted to affect both life span and fertility.